The

eCOTOOL

Competence

Model

| Keywords | skill, competence, model, ability, framework, structure |

|---|

| Abstract |

The eCOTOOL Competence Model is a general purpose model covering both the internal structure of a definition of competence, skill, ability, or similar concept, and structures of these. It was developed to achieve more functionality in a more general way than purely within a Europass Certificate Supplement. It is offered as a contribution to the solution of the real problem of representing and communicating information about competences and related concepts and structures, and for making tools that handle such information interoperable, so that any tool can manage information associated with any competence. |

|---|

| Authors / Reviewers / Contributors of this Document | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Organization | Country | Role |

| Simon Grant | University of Bolton | UK | Lead author |

| Christian M. Stracke | University of Duisburg-Essen | Germany | Author |

| Charalampos Thanopoulos | Agro-Know | Greece | Author |

| Cleo Sgouropoulou | ELOT | Greece | Author |

| Carolyn Owen | MAICh | Greece | Author |

| Lenka Fišerová | UZEI | Czech Republic | Author |

(Reformatted as one of Simon Grant's eCOTOOL publications within Simon Grant's publications)

2. Introduction and background

2.1. Relationship to the Application Profile

2.2. The Europass Certificate Supplement

2.3. General uses of competence definitions

2.4. Combining competence definitions in structures

2.5. Examples of fuller competence structures

2.5.1. UK National Occupational Standards

2.5.2. UK vocational qualifications

2.5.3. German vocational regulations

2.5.4. Czech National Register of Vocational Qualifications (NSK)

2.5.5. Greek competence structures in Vocational Profile descriptions

2.5.6. Review of competence structures

3. The eCOTOOL Competence Model (High-Level)

3.1. Purpose and contents of the high-level model

3.2. High-level model terms and definitions

3.3. The eCOTOOL high-level model of an ability item

3.3.1. Primary components of the high-level model

3.3.2. Unique id codes for cross-referencing ability items

3.3.3. Attribution of levels to ability items

3.3.4. Further classifying ability items

3.3.5. Constructing high-level model ability items

3.4. The eCOTOOL high-level model of competence structure

3.5. The eCOTOOL high-level model of level definitions

3.6. Using the forms to define competence in your field

3.7. Profiles of personal ability or job requirement

3.8. General guidance for structuring competence

3.8.2. Working from employment requirements

3.8.3. Working from curriculum subject areas

3.9. Granularity for different purposes

4. Using competences in Europass documents

4.1. Constructing ability items for Europass Certificate Supplements

4.2. Competence in other Europass documents

5. The eCOTOOL Competence Model (Technical)

5.1. Purpose and content of the technical model

5.2. Technical and other additional terms and definitions

5.3. Moving from high-level to technical model

5.4. Representing separate ability or competence concepts

5.4.1. The uses of ability and competence concepts

5.4.2. Structure of an ability or competence concept definition

5.5. Representing structural relationships

5.6. Cross-mapping relationships

5.7. Representing level definitions

5.8. Representing competence frameworks and standards

5.8.1. The uses of competence frameworks and standards

5.8.2. Inclusion of competence concept definitions within frameworks

5.8.3. Structure of a competence framework

5.9. Map of the information model

5.10. Relating back to the Europass Certificate Supplement

6. Conclusions in terms of refining and extending the ECS application profile

The application profile (AP) of the Europass Certificate Supplement (ECS) deliberately omitted any detailed model of competence structures, as these would not be implemented in the eCOTOOL prototype tools. This more detailed competence model is offered as a refinement and extension of the ECS AP.

Competence definitions and structures can play several roles: employers may want to specify their recruitment requirements or organise their training; individuals may want to plan and review their training, and present claims of their abilities; training bodies may wish to use competence definitions to inform their learning outcomes; industry bodies may want to define the skills and competences required in their industry, acquired through training. A model of competence has to be able to serve any of these roles.

Particular competences claimed, or learning outcomes sought, need to be defined in their own right, but some depend on, or consist of, other narrower ones, and structures relating the definitions together need to be modelled as well.

For ease of comprehension, the eCOTOOL Competence Model is presented in two stages, and terms appropriate to each stage are defined in the model. Where it is possible and appropriate, the definitions follow those to be found in related works.

The “high-level” model is explained in terms of filling in three forms: a first one (“Form A”) for each separate definition; a second one (“Form B”) each time a broader definition is analysed into narrower ones; and a third one (“Form C”) for defining fixed levels of a variable competence. In this high-level approach, some simplifying assumptions are made and some guidance is given to help people write competence structures, particularly for the ECS. The role of competence definitions in other Europass instruments is discussed briefly, for comparison and contrast.

The “technical” model gives more generality, and is presented in a way that relates closely to a technical information model. It would be straightforward to define formal information models from this, and from there to define bindings to specific technologies that would enable the creation of interoperability specifications for these kinds of information.

Competence concept definitions are technically modelled separately from competence structures. The concept definitions themselves are kept with a limited scope, to maximise the ability to reuse the definitions. The structures, referred to here as “frameworks”, in line with common usage, include decomposition into necessary and optional parts, and level definitions.

The attribution to a competence concept definition of a level in another level scheme differs from the definition of a new level scheme in its own terms. Such attributions can be represented either within a separate competence concept definition, or within a competence structure. Also, categorisations of competence concepts, and their relationships with concepts in other structures, can be represented wherever convenient.

Several diagrams are given to illustrate the relationships between all these concepts related to definitions and frameworks.

One of the outcomes of the eCOTOOL project is to develop a representation of the Europass Certificate Supplement (“ECS”) for ICT purposes. The purposes of the eCOTOOL competence model go beyond this, but the ECS serves as a good anchoring point for the competence model. Section 3 of the ECS includes a list of “skills and competences”, and items similar to the ones in Section 3 lists could be used in a variety of ways. Section 3 items might best be drawn from a larger competence framework, and the modelling of such broader competence frameworks is another key area that the eCOTOOL competence model is intended to clarify.

In Deliverable 1.2, an Application Profile of the ECS was presented. The detail in which the ECS Section 3 should modelled was considered carefully, and it was concluded that there was a need for a much richer representation of skill and competence information in order to lay the ground for and facilitate ICT tools that will not only allow people to represent skills and competence more fully, but also to build the kind of structures that are essential to understanding the way in which skills and competences in a vocational area are structured.

However, the model implicit in the ECS Section 3 is very restricted. In order to allow good progress with the project’s work, it was decided to deliver just the essential structure of Section 3 in the Application Profile, and to work on the “eCOTOOL Competence Model” as a refinement to that specific area of the Application Profile.

The articulation between this deliverable (D1.4) and the earlier one (D1.2) is subtle. Because of the way in which D1.2 was presented, it is quite self-contained, and the need for refinement may not be obvious at first sight. Equally, this deliverable (D1.4) needs to be a general purpose model of skill and competence definitions, and as such the ECS may not at first sight appear closely connected. But, on deeper analysis, it the strength and necessity of the connections become apparent. The task of constructing an ECS Section 3 is made much more practical by having a fuller structure to select from, and the relations between the items chosen for Section 3 and other definitions can be clearly identified in a wider model. Equally, a wider model of competence needs to be anchored to a practical purpose, and related to the learning outcomes that are required in a particular occupational domain. Having a goal such as the ECS is a helpful target, because the ECS itself aims to help bridge the gap between vocational training and the needs of employers.

The official Europass web page used to state that the "Europass Certificate Supplement is delivered to people who hold a vocational education and training certificate; it adds information to that which is already included in the official certificate, making it more easily understood, especially by employers or institutions outside the issuing country."

The officially produced "Guidelines for filling in the Europass certificate supplement" state that the ECS "contains a detailed description of the skills and competences acquired by the holder of a vocational education and training certificate". Section 3 of the ECS is headed "Profile of skills and competences", and the Guidelines for filling in that section state that Section 3 "gives a concise description of the essential competences gained at the end of training" — what “a typical holder of the certificate is able to” do — in other words, it is a list of typical abilities. They further recommend that:

This advice is helpful and appropriate, but it does not greatly help the formulation of the most useful ability items. Bodies writing ECS documents have not consistently followed this official ECS advice, suggesting that it may be confusing. The present document offers a model of competence designed to help people more effectively compose ability items for the ECS Section 3.

The ECS Section 3, the “profile of skills and competences”, is designed to convey what has been covered in a VET course. While the individual lines of Section 3 — the ‘ability item short definitions’ — may be formulated in a particular way for the purposes of the ECS, the underlying concepts are relevant to various different purposes.

Here are some examples of Section 3 ability item short definitions, which have not been specially selected, but give some indication of the kind of ability item short definitions seen in Section 3.

First, from the English translation of a Greek ECS for “viniculture — vinification technician”, prefaced by “The holder of this certificate:”

“prepares the soil for seeding, selects the multiplying material, seeds and installs maternal plantations / grafts”

Next, from the English translation of an Italian ECS about “agritourism services operator”, prefaced by “The Certificate holder is qualified to:”

“organise, with competent agriculture authorities, methods of rural hospitality”

Finally, from an English ECS in a completely different area, for “City & Guilds Level 2 NVQ in Domestic Natural Gas Installation and Maintenance”, prefaced by “A typical holder of the certificate is able to:”

“Service and maintain domestic natural gas systems and components

None of these are perfect examples according to the ECS documentation. But these and similar examples can still be imagined playing various roles beyond the ECS Section 3, including helping to structure a training course, or the assessment of abilities in the respective areas.

Competence concept definitions, or just “competence definitions”, define the competence concepts that are used in many ways beyond the ECS Section 3. ECS Section 3 ability item short definitions are one kind of competence definition. Listed below are many of the principal uses of competence definitions, which can help inform their writing. Explanation follows.

One can easily imagine employers using wording similar to ECS Section 3 ability item short definitions in a description of what a job involves. The wording may be rather too detailed for a job advertisement, but it could still be read by an applicant for a post to help them understand what the job involved, and whether they were in fact able to meet the requirements of the job.

The use of competence definitions throughout large organisations is widespread, but there is less public awareness of it, partly because businesses often regard their own frameworks of skill and competence as commercially confidential, rather than making them public. If a business is to manage its workforce competences, they will need competence definitions that are understandable by all concerned. Often these are discussed in HR circles under the term “competencies” (plural of “competency”). There is sometimes a distinction made between “competency” and “competence”, but this will not be discussed here.

Individuals need be clear about the abilities or competence they are claiming in their CVs or portfolios. While these descriptions would typically not be skill headings in a CV, as they are too detailed, similar wording might appear in a detailed description of a job that a person has done in the past.

When recruiting, it is vital that employers can assess the abilities of potential employees. It is also very helpful if individuals can assess themselves, so that they can plan for the development of their abilities and competence. In each case, one can imagine an expert observing someone less experienced in a role, and assessing whether they are competent at performing these activities, and perhaps acting as part of a checklist to inform a junior employee about where they need to get more experience and develop their competence.

Competence concepts appear in occupational frameworks. In practice, when frameworks are being devised, often the individual definitions are written at the same time. It is also possible that a framework could include previously established competence definitions, including those from other frameworks.

In each case, one can imagine courses whose syllabus covers these areas. However, they are not well adapted to form the kind of learning outcomes that are typical, at least in higher education.

This has been a goal for many years. A learner may have a long-term goal of employment in a particular occupation. If there is one suitable course that prepares them fully for that occupation, they may take that, but in an increasing number of cases it is not that simple. Courses proliferate, and one single course may just give some of the abilities needed, or may prepare for further learning education or training by giving the learner skills that are pre-requisites for the further course that is actually going to prepare them for employment.

In these cases, finding a good pathway from a learner’s starting point to employment may be daunting, if not so hard as to effectively block many learners from attaining their employment goal. Given that the time of expert careers advisors is costly and rare, what is needed is effective automated help for learners to find their way through what can seem like a maze of learning education and training.

The clear mapping of both learning outcomes and prerequisites (for higher courses and for actual employment) will provide the basis for tools to offer effective help in this area, guiding more learners from their present starting point to economically valuable employment.

The fact that the wording of a competence definition in general could potentially be useful in several different contexts does confirm that we are dealing with an important topic. However, the more precise requirements for each use do differ. Therefore, the wording of the ECS ability item short definitions should not in itself be taken as definitive of the underlying concept, but simply as a form that is taken as suitable for the particular application of the ECS itself.

Writing ability items in isolation is possible, but is by nature an incomplete activity. In the longer term, it is likely to be more effective to construct fuller structures defining competence, abilities, skills, and underlying knowledge, at a variety of different useful granularities, within particular domains. This is, however, a much more demanding task. There are many examples of fuller structures that have been written to document competence and abilities. Fuller structures can potentially be the source not only for ability item short definitions for ECS Section 3, but also for intended learning outcomes for learning, education and training (LET) courses. In the following section, some better-known examples of these fuller structures are presented. Later on, the present document:

Where a fuller structure has been constructed, it may be possible to choose items at suitable granularities within that structure to serve as ability item short definitions for an ECS Section 3. Even where suitable items are not immediately available, a fuller structure makes it easier to define appropriate ability items. Thus, the present document:

Within Europe, perhaps the largest body of consistent structures related to occupational competence is the UK’s collection of National Occupational Standards (NOS). The NOS database is on a website where all current NOS can be viewed. The body with current overall responsibility for NOS is the UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES), who publish NOS quality criteria (UKCES, 2010) and a guide for NOS development (Carroll & Boutall, 2011)

NOS are developed principally by Sector Skills Councils, and the one in the UK closest to eCOTOOL’s trial area, agriculture, is LANTRA, the UK’s Sector Skills Council for land-based and environmental industries.

NOS developed by LANTRA are no different in principle from any other NOS, and generally follow the guidelines maintained by the UKCES. LANTRA’s NOS documentation consists of PDF files each covering an occupational area, e.g. treework. The treework document includes 54 NOS specific to treework, and several more general ones. Each single NOS covers a single function that can be performed by an individual, such as “fell small trees using a chainsaw”. This NOS is divided into three elements, and each element contains a list of performance criteria (“what you must be able to do” to reach the standard) and a list of “what you must know and understand”. There are 10 performance criteria for the element 10.2 “Remove branches from small trees using a chainsaw”, including such items as:

“2. Meet specified legislative and organisational environmental requirements when de-branching small trees”

“7. Remove branches from (sned/ de-branch) felled trees using an organised method appropriate to tree form and condition”

“10. Ensure resultant brash is stacked, removed or broken down as appropriate to site specification.”

The required knowledge and understanding starts with (a) How to identify hazards and comply with the control procedures of risk assessments when de-branching small trees (b) Emergency planning and procedures relevant to site (c) How and why to initiate and maintain effective communication when debranching small trees”. The most usual practice for NOS is to have the performance criteria, and requirements of knowledge and understanding, as immediate parts of a single “NOS”.

This should give an initial idea of the kind of content typically found in NOS. There are very many more examples freely available on the relevant websites.

LANTRA has not yet produced any Europass Certificate Supplements.

City & Guilds is probably the largest UK body involved in awarding vocational qualifications. Their website gives figures of 1.9 million certificates awarded each year, with over 1000 employees in the organisation itself. City & Guilds often offer a Europass Certificate Supplement along with their qualifications.

Vocational qualifications in the UK are related to the Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF – see explanation on the gov.uk site), which shares the UK’s NQF levels. The NQF levels are not identical to EQF levels, but are very similar.

A brief look at level 1 and level 2 qualifications confirms that many of these lower-level qualifications are limited in extent, and may be quick to complete. In order to build these small qualifications into something that counts in the workplace, vocational awarding bodies often specify pre-requisites for qualifications that are not the very first ones to be taken. But these dependencies are only indirectly relevant to the occupational frameworks themselves.

What is more significant is that the intended learning outcomes specified for assessment in the qualifications, and therefore for learning, education or training leading up to those qualifications, may be related to NOS.

For example, City & Guilds have a level 2 award in chainsaw operations, for which one has to complete two core units. Each unit has a detailed assessment schedule. There is a Europass Certificate Supplement for the award. One can easily see the connections between the assessment schedule and the ECS, and with more effort between these and the LANTRA NOS in this area. But there is much that could be made clearer and more transparent.

In Germany there is a dual system for vocational education and training (VET), shared between the public and private sectors. VET takes place in companies and part-time vocational schools. Training regulations govern the organization of this dual system. For example, there is one entitled “Verordnung über die Berufsausbildung zur Fachkraft Agrarservice” (Bundesanzeiger Verlag, 2009) for agricultural service specialists. The plan for the VET “Ausbildungsrahmenplan, Ausbildungsberufsbild” is divided into two sections, one for building the “professional profile” (“Berufsprofil”) and one of more general and transferable abilities (“Integrative Fertigkeiten, Kenntnisse und Fähigkeiten”). For instance, the occupation specific section (“Berufsprofilgebende Fertigkeiten, Kenntnisse und Fähigkeiten”) includes a heading (5) for crop production (“Pflanzenproduktion”) which has three subheadings, in German:

Annex 3 sets out the detail of these headings and subheadings. For example, 5.1 (“Bodenbearbeitung”) is expanded to:

These are recognisably similar in form to, for instance, the performance criteria of a UK NOS. They can be translated as sentences starting with action verbs. The other headings are expanded similarly. There is a great deal of other information and material present in this and related documentation, but the essential structural aspect is nevertheless clear.

The NSK register has been developing in the Czech Republic since 2005. It will provide information on qualifications from across education and training. The NSK is a publicly accessible register of all full and partial qualifications. The framework for these qualifications consists of eight levels similar to the EQF levels. Representatives of employers associations and sector councils are involved in the process of designing and approving the qualifications to ensure their high quality.

NSK distinguishes between two types of qualifications.

Each partial qualification contains a list of expected competence-related learning outcomes (“Odborná způsobilost”). For example, “Grower of basic crops” has 7 of these competence-related learning outcomes, one of which is “Sowing and planting crops” (“Setí a sázení zemědělských plodin”).

The learning outcomes cover of the knowledge, skills or competences required for a specific work activity or activities in a particular occupation. These are the assessed to obtain the relevant qualification.

Each learning outcome has a list of knowledge or skill related assessment criteria for that outcome, alongside methods for validating the knowledge or skills required in a particular activity. For example, “Sowing and planting crops” gives the following list, where each criterion is followed by the assessment method (roughly and informally translated here into English).

The lists of learning outcomes and assessment criteria are published at www.narodnikvalifikace.cz

As with the German structures, the structure of the Czech NSK is clearly recognisable. The fact that it is focused mainly around qualifications rather than occupational roles is only a minor issue, as the two are closely related. The assessment methods do not strictly belong inside a competence model, as the same competence can potentially be assessed in different ways, but the assessment criteria are in effect of the very same nature as the performance criteria and underpinning knowledge and understanding that are seen in the UK NOS.

The National Accreditation Centre for Continuing Vocational Training (EKEPIS), a statutory body supervised by the Minister of Employment and Social Protection with administrative and financial autonomy, determines the national occupational standards for the description of Vocational Profiles in Greece.

A “Vocational Profile” is defined by the main and secondary occupational functions that constitute the object of work for a profession or specialty, and the knowledge, skills and competences required to respond to these functions. The main objective of vocational profiles is the structured analysis and recording of the content of occupations and of the ways to acquire required qualifications.

According to this definition there are three key components of the vocational profile that are given special attention during its development:

On this basis, the specification of vocational profiles has five key constituent sections.

More specifically, the analysis of the profession / specialty is carried out in four levels:

The occupational profile is analysed in main (basic and secondary) occupational functions and occupational activities. Occupational activities are connected to competences, skills and knowledge (generic, basic occupational and specific occupational). The occupational profile is structured as follows:

Here is an example of the analysis of the job: Farmer — manager of Agro touristic farm

The occupational profile technical guide also proposes possible training opportunities for someone who would like to acquire the specific competences that are related to the successful accomplishment of the job tasks. Also, some useful suggestions are included for the assessment of the acquisitions of all these knowledge, skills and competences.

This Greek example shows a common pattern of putting together competence-related definitions with specifications for assessment, and other career-related information. For a competence model, we need to set aside the information about legality, procedures and assessment, and focus on the content of the “content of the occupation” and the constituent sections (above) A, B and C. Analysing this core content, again we see what looks essentially like a tree structure, though the branching levels differ from those seen for other countries.

The detail of the way that competence structures are set out differs from country to country. Nevertheless, the constituent parts are easily recognisable, particularly through examples. These examples of existing competence structures clearly point to the need for a flexible model, equally capable of representing the different structures.

The high-level version of the eCOTOOL Competence Model is developed to be used with and by people involved with competence definitions for any practical reason. Because the needs of these stakeholders differ from the needs of technical systems developers, further technical details are presented only in the technical version, which follows this high-level model. This high-level model is high-level in that it omits much lower-level detail that is relevant to technical systems developers, but not directly relevant to stakeholders with a direct practical involvement.

The eCOTOOL Competence Model (High-Level) consists of:

Ability:

characteristic of a learner indicating something that the learner is able to do

(Abilities may normally be described in brief with a clause starting with an

action verb. The definition of a particular ability concept is here termed an “ability

item”. The EQF uses the word “ability” in the definition both of skill and of

competence. Many learning outcomes are also abilities.)

Ability item: definition of a particular ability concept

(An ability item short definition should start with an action verb, and form

a meaningful sentence when used to finish a sentence starting with words such

as: “This person is able to ...”. For example, “prepare the soil for seeding”.

In English, this has the same form as a direct instruction.)

Action: something that is or can be done by a learner; part of an activity

Action verb: word or phrase expressing an action or activity

(e.g. “manage”, “oversee”, “construct”, “lead”, “diagnose”, “develop”,

“prepare”, “organise”, “demonstrate”, “act”, “record”, “build”, “plant”,

“state”, “explain”, “choose”, “pick up”, etc.)

Activity: set or sequence of actions by a learner, intended or taken as a whole

(An activity may be focused on the performance of a task, or may be

identified by location, time, or context. Activities may require abilities.)

Competence: proven ability to use

knowledge, skills and personal, social and/or methodological abilities, in work

or study situations and in professional and personal development [EQF]

(In the context of the European Qualifications Framework, competence is

described in terms of responsibility and autonomy. It involves selecting and

combining knowledge and skills for the performance of tasks in practical

situations or contexts.)

Educational level: one of a set of terms, properly defined within a framework or scheme, applied to an entity in order to group it together with other entities relevant to the same stage of education [EN 15981]

Knowledge: outcome of the assimilation of information through learning [EQF]

(Knowledge is the body of facts, principles, theories and practices that is

related to a field of work or study. In the context of the European

Qualifications Framework, knowledge is described as theoretical and/or factual.)

Learner: individual engaged in a learning process [ECTS Users Guide]

(The term “learner” may be replaced throughout this document with the term

“person” with no change of meaning. Learners may also be employees. All people

are here regarded as learners.)

Level: (a) educational level (q.v.) (b) occupational level (q.v.)

(NOTE: Not to be confused with the use of “level” in this document as “high-level

model”.)

Occupational framework: description of an occupational or industry area, including or related to job profiles, occupational standards, occupational levels or grades, competence requirements, contexts, tools, techniques or equipment within the industry

Occupational level:

one of a set of terms, properly defined within an occupational framework,

associated with criteria that distinguish different stages of development

within an area of competence

(This is often related to responsibility and autonomy, as with the EQF

concept of competence. There may be some correlation or similarity between the

criteria distinguishing the same occupational level in different competence

areas.)

Skill: ability to apply knowledge and use know-how to complete tasks and solve problems [EQF]

(In the context of the European Qualifications Framework, skills are

described as cognitive (involving the use of logical, intuitive and creative

thinking) or practical (involving manual dexterity and the use of methods,

materials, tools and instruments). They can be practically demonstrated with

the help of appropriate tools or equipment.)

Task: specification for learner activity, including any constraints, performance criteria or completion

criteria

(Performance of a task may be assessed or evaluated.)

Refer to Form A, shown in Tables 1 and 2 below.

According to the eCOTOOL competence model (high-level), an ability item short description has two parts:

When composing an ability item, it may be a good idea to start by writing a first short description representing briefly the essence of what the ability is. If this description does not already start with an action verb, it is recommended in most cases to search for a suitable one. Some more advice can be found below to ensure good quality items with appropriate action verbs.

There are two particular cases where finding an action verb might be problematic, and therefore an action verb is recommended but not mandatory.

The high-level model allows the classification of each ability item into one of the “KSC” categories:

These terms have been defined above, and are now explained further.

All practical abilities rely on some knowledge, but when you write down what is necessary for competence at some role, job or occupation, it is essential to make the distinction between plain knowledge, and abilities that may use that knowledge. You can test any knowledge (together with purely cognitive abilities) through traditional non-practical examination methods such as multiple-choice questions, written answers, face-to-face question and answer. To test practical abilities properly, in contrast, these approaches are not enough: some practical setting or equipment is needed.

Distinguishing two kinds of practical ability is often straightforward: What is here called "skill" can be tested on demand in any practical test setting, given appropriate equipment; while what is here called "competence" can only be tested by observation in a live situation, and be properly judged only by an expert. Both will involve some knowledge, whether explicit or implicit. Competence will also involve skills, but as well as testing the skills separately, the competence as a whole needs to be tested.

Here is a summary together with some guidance on action verbs.

Particularly when mixing ability definitions from different sources, it is very useful to keep track of the author or authority of the item. Abilities themselves are qualities pertaining to people; it is the ability items — authored by particular people or bodies — that set out a form of words in which that ability is described. You are the author of the ability item definitions that you create, but you may also borrow ones that are authored by other people or bodies.

If you work with many ability items, you probably recognise that the same narrower ability may play a vital part in more than one broader ability. It is also convenient to separate the definition of individual ability items from their place in structures. For both of these reasons, it is very useful to create a unique id code for each ability item. You can make up the code entirely to suit yourself, perhaps with a very few letters or numbers, to help recognition and reuse. It can be any short code, to help keep track of ability items you have across the several separate tables that are used in the model. It only has to make sense to you, and the only condition is that you must have a different code for every different thing in your framework or structure.

In some existing competence structures, codes have already been devised. For instance, the LANTRA NOS (national occupational standards) have their own short codes for each unit, and each element within a unit. “Set out and establish crops” has code PH2, while the element “Set out crops in growing medium” is PH2.1 and “Establish crops in growing medium” is PH2.2. LANTRA does not give codes to any of the narrow individual ability components of an element.

Often, abilities are described as being at specified levels. It is often the case that education, training, and professional development result in learners progressing from lower levels of ability to progressively higher levels. However, there is no uniformity, either in educational or occupational level schemes, about the number of levels, or terms used to describe them. In recent years, the European Qualifications Framework for Lifelong Learning (EQF) has been introduced in an attempt to aid the cross-mapping of different level schemes. It defines eight levels in each of the three areas of knowledge, skills and competence. The EQF is intended to serve more as a neutral reference point than a single common standard.

A person defining a competence structure or framework may use the EQF to state that they have judged a particular ability item as fitting best with the selected EQF level. In the eCOTOOL high-level model of levels, users can judge the level of an ability item in any level scheme or framework that is familiar to them. For cases where no level scheme is currently recognised as appropriate by the user, any simple level scheme can be adopted. WACOM, a sister project to eCOTOOL, proposed this five-level scheme, and here it is explained in relation to the EQF levels.

Items can have any number of different levels attributed, or none, but within each level scheme or framework, only as many levels as are allowed by that scheme. Courses of education are often given a single level within ISCED, UNESCO’s International Standard Classification of Education, as well as being mapped to EQF via a national scheme or framework of levels, either overall, or potentially separately on the EQF’s knowledge, skill and competence levels.

There are also very many small-scale level schemes, including ones you may create yourself (for details of doing this see below). To avoid ambiguity, one must always indicate which framework or scheme is being used, when attributing any level. Other people may not make the same assumption about level scheme as you do.

Ability items can be categorised for any of several purposes, beyond the KSC categories. It may, for example, be useful to record where appropriate: Standard Industry Codes; Standard Occupation Codes; library-oriented subject matter categories; any education or training categories; professional body categories, etc. Levels are not dealt with as categories.

For any categorisation, you will need to specify the classification scheme, and the term from that scheme. An item may be classified under any number of schemes, or none.

A table with the recommended elements is given here as Table 1: Form A. This form can be filled in for as many ability items as are relevant to the person or organisation documenting their competence concepts. Guidance on when to stop is given later.

A full description of the ability should be given in any case, even if this simply repeats the set of definitions of narrower abilities that make up the ability being defined.

Table 1: Form A: item definition form

| Form A: eCOTOOL high-level model item definition table |

|||

| ability item |

action verb(s) |

rest of short description |

|

| KSC category |

knowledge☐, or skill☐, or competence☐ |

||

| unique id code |

|||

| author/authority |

|

||

| level attributions |

level scheme |

level |

|

| (repeat as needed) |

|||

| categorisation |

classification scheme |

term |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (repeat as needed) |

|

|

|

| full description |

|

||

It is very common to see ability items described or defined together in some kind of structure, such as an occupational framework. Occupational frameworks and other such structures differ in what they cover, how broadly they extend, and in the way that ability items are related within them. The eCOTOOL high-level model is designed to be easy to use, allowing the majority of current occupational frameworks to be structured in a common way.

There are two principal alternative approaches to creating competence structures. One approach starts at the top with a job requirement, and progressively breaks that down into the constituent (subsidiary, narrower) parts; another approach identifies abilities at all levels, and works out which ones are parts of which other ones. In order to allow both approaches, the eCOTOOL high-level competence model keeps separate track of the ability items on the one hand, and the structure information on the other. Every relevant item at every granularity (except perhaps the narrowest) needs to have a definition outlined as in the previous table. The unique id codes, along with short descriptions for readability, are then used in table to show which narrower abilities are parts of which particular broader ability.

Before showing the breakdown of a particular ability item, we start with an example of what a particular ability item definition could look like. The example is taken from the UK City & Guilds Level 2 NVQ in Domestic Natural Gas Installation and Maintenance.

Table 2: Form A filled in for a particular example, ready to be given structure

|

Form A: eCOTOOL high-level model item definition table |

|||

| ability item |

action verb |

rest of short description |

|

| service and maintain |

domestic natural gas systems and components |

||

| KSC category |

knowledge☐, or skill☐, or competence☑ |

||

| unique id code |

GC08 |

||

| author/authority |

UK City & Guilds |

||

| level attributions |

level scheme |

level |

|

| UK NQF |

2 |

||

| EQF |

3 |

||

| WACOM |

2 |

||

| categorisation |

classification scheme |

term |

|

| UK SOC2010 (see the web page for further info) |

5314 |

||

|

NACE (see the web page for further info) |

F43.2.2 |

||

| full description |

Ensure that there is sufficient information available to determine the maintenance requirements; service and maintain the stated range of appliances and systems; record the maintenance activities in the appropriate media; diagnose and rectify faults in the stated range of meters and systems; take precautionary actions to prevent use of unsafe installations. |

||

To express the structure of this, Form B is used. Structure information defines which parts make up the whole. The parts can be necessary, in which case claims or requirements for the broader item imply the narrower ones; or optional. Optional parts are not strictly implied, but they give other components that may or may not be claimed or required.

The simplest case is where a broader competence concept is broken down into necessary narrower abilities, which are all essential requirements of the overall ability. As this is the easiest example to understand, an example of this is given here, based on the competence concept introduced above.

Table 3: Form B filled in for the example above

| Form B: eCOTOOL high-level model structure information |

|||

| ability item |

service and maintain domestic natural gas systems and components |

||

| unique id code |

GC08 |

||

| author/authority |

UK City & Guilds |

||

| narrower concepts |

the narrower concept |

unique |

Necessary |

|

|

ensure that there is sufficient information available to determine the maintenance requirements |

GC08-S01 |

N |

|

|

service and maintain the stated range of appliances and systems |

GC08-S02 |

N |

|

|

record the maintenance activities in the appropriate media |

GC08-S03 |

N |

|

|

diagnose and rectify faults in the stated range of meters and systems |

GC08-S04 |

N |

|

|

take precautionary actions to prevent use of unsafe installations |

GC08-S05 |

N |

Filling in a Form A for each narrower concept is then possible.

Occasionally, rather than a decomposition into necessary parts, there is a genuine choice of different ways to approach or perform a task, or fulfill a role. Examples include management competence. There are different styles of management, and many lead to reasonable results in many situations. The skills needed in these different management styles vary but overlap. Most managers will have a particular personal style, so they will be competent at one or more options, but typically not all. Or, take an example from agriculture. You may want to represent competence in growing different types of crop. Farmers are not expected to be experienced at growing every type of crop, or every different kind of horticulture. The aim here is not to be definitive or comprehensive — that is the job of classification schemes. It is to list the types of ability relevant to the framework under consideration, for whatever reason.

A similar kind of structure is also commonly used for qualifications. Typically there are core abilities that every learner is expected to master, but also often optional specialisms. This is a potentially problematic issue for the Europass Certificate Supplement, in which there is no guidance on optional knowledge or abilities. There are many examples of structures with optional parts for qualifications, but none that adequately represent different ways to approach a task, so it is a qualification example that is used to illustrate this.

This example is taken from an old UK Level 1 NVQ, found on the web site of a volunteer organization, where it does not explicitly name the authority.

Table 4: Form B for a qualification structure with options

| Form B: eCOTOOL high-level model structure information |

|||

| ability item |

Horticulture NVQ Level 1 |

||

| unique id code |

Hort-L-1 (invented for use here) |

||

| author/authority |

(some vocational awarding body) |

||

| narrower concepts |

the narrower concept |

unique |

Necessary |

|

|

Maintain safe and effective working practices |

CU1 |

N |

|

|

Assist with planting and establishing plants |

CU61 |

N |

|

|

Assist with maintaining plants |

CU62 |

N |

|

|

Transport supplies of physical resources within the work area |

CU8 |

O |

|

|

Assist with the maintenance of grass surfaces |

CU15 |

O |

|

|

Assist with maintaining structures and surfaces |

CU16 |

O |

|

|

Assist with the maintenance of equipment |

CU17 |

O |

|

|

Assist with the vegetative propagation of plants |

CU63 |

O |

|

|

Assist with the propagation of plants from seeds |

CU64 |

O |

In this example, there are three necessary (mandatory) units and six optional units. From the point of view of representing the structure, it is not immediately important how many of these optional units are required, though in this case it happens to be three. The fact that three options are needed is best represented in the full description of the item. Any particular claim, or perhaps the actual certificate given to the learner on completion, may list which options have been taken. If the person has the competence described by the whole qualification, that implies having the first three necessary (mandatory) abilities. But none of the other ones are certain. To make a full claim of competence, the learner has to specify which options were taken. An employer may want to specify (though it is unlikely at this level) which of the options are required for a particular job.

Levels may be defined where a single ability concept can be claimed or required at different levels. Each level may have its own descriptors or criteria, but these normally overlap considerably, rather than being distinct in the way that constituent parts are distinct. Form C is used to define your own levels.

If an existing level system, framework or scheme is sufficient for your needs, then you will not need to do this. But in many occupational competency and other frameworks, the creators find it convenient to define their own level scheme. It may also be that a level scheme has already been devised. In this case, you may just want to enter the information in this form, with the idea that it might be transferred to an ICT system later.

To define your own levels, start with the competence concept that does not yet have levels, but to which you want to add levels. You can document this in the same way as other ability items, with Form A. Then choose how many levels you are going to define. On Form C, give each level a number, with a higher number representing more ability or more competence; a definition of, or criteria for, ability at that level; and optionally a label that identifies the level, alongside the number. If you wish to analyse or break down these level definitions, you will then need to give them unique id codes and treat them like a constituent part or a variant type or approach, and fill in a Form A for each one that you want to break down or analyse further.

Here is an example based on material from the UK’s QAA Subject benchmark statement for Agriculture, horticulture, forestry, food and consumer sciences (QAA, 2009). In its Section 6 the document “articulates” the standards expected of graduates from UK degree courses,

“at three levels: 'threshold', 'typical' and 'excellent'. These are defined as:

This is an example of how an eCOTOOL high-level model level definition could be written based on a small part of that statement, somewhat rearranged. The numbers are added, but are suggestive of the way that many educators and trainers think in terms of the scores in assessment tests, often as in this case out of 100.

Table 5: Form C for level definitions

|

Form C: eCOTOOL high-level model level definition |

|||

|

ability item |

recognise and explain ethical issues related to agricultural production systems and biology |

||

|

unique id code |

Agri-2-ethics (invented for use here) |

||

|

author/authority |

based on UK Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education |

||

|

where level |

QAA Subject benchmark statement for agriculture horticulture etc., ISBN 978 1 84979 017 8 |

||

|

levels |

definition of each level |

level |

level number |

|

|

recognise the ethical implications of production systems; have some familiarity and awareness of ethical issues related to agricultural practice |

Threshold

|

30 |

|

|

recognise and address the ethical implications of production systems; have a well-grounded understanding of ethical issues related to the use and exploitation of biological entities |

Typical |

50 |

|

|

recognise, anticipate and address the ethical implications; have a deep and comprehensive understanding of ethical issues related to the use and exploitation of biological entities |

Excellent

|

70 |

You will also notice a field for where the level scheme is defined. If you are structuring an existing framework, as in the example, you can put here a reference to or note about where the level scheme is defined. If, on the other hand, you are defining a fresh new level scheme, you have at least two choices. First, if you want to define all the levels separately, with no common features, then you can leave the field blank, or put “here”. Second, if you want to define a generic level scheme, define the levels alongside the competence definition that encompasses all the usage of that level scheme, and when you use that level scheme, put that competence definition unique id code in the box for where the level scheme is defined.

Two possible scenarios are envisaged for the practical use of the eCOTOOL high-level competence model. One is that you may be putting an existing framework or structure into the eCOTOOL model format; the other is that you may be creating a framework or structure from scratch. The procedures in both cases have many similarities, but the main difference is that when you are creating new definitions, you do not have existing materials to work with, so you are likely to want to revise much more as you go along.

In both cases, it makes sense to start by focusing on the ability item definitions. Fill in Form A for as many different abilities as might reasonably be claimed, required, learned, or assessed separately. It is these definitions with Form A that are central to the value and reuse of the framework. Then fill in Form B for as many ability items as can be broken down into narrower items. You can if you like also fill in a Form B without narrower unique id codes, if you want to list the parts of some ability, without needing to represent those parts separately for any reason.

Use Form C only if you define levels (but not if you only attribute other authorities’ levels to ability items). The point of Form C is to define levels according to you, not according to any other authority. If you define numbers for levels appropriately, then people will be able also to claim their level of ability with a number between the numbers you have defined (e.g. 63 in the example above).

Your model of competence in your area is useful to the extent that people agree on it and use it. The more people you are able to draw into agreement in the definition process, and in refining the definitions, the more useful your structure or framework is likely to be.

The forms above are intended for the definition of reusable competence-related structures, and not for claiming or requiring sets of abilities. Anyone can, if they wish, construct a personal profile of their abilities, or a profile of abilities required for a job, by creating a list referring to defined ability items. The structure information helps you, because if you claim or require a broader ability, you are implicitly claiming or requiring all the necessary narrower abilities. But if a narrower ability is optional, you must list it explicitly in a claim or requirement. In claiming your ability as defined with optional parts, you are also claiming that you fulfil any constraints on the number of optional parts you are also claiming, otherwise you should not be claiming the broader ability.

Where an ability item is defined as having levels, as an option, instead of quoting the whole definition of the level, you can give the ability item title plus the level id code and/or number claimed / required. This number may or may not be one of the ones with a specific definition. You can also add external levels if you believe they can apply to the ability you are claiming.

Review all ability concepts as you draft them, asking yourself whether, and checking that, your formulation can readily be used, both:

If a set of fine-grained abilities are never realistically going to be separated in: a personal claim; evidence for such a claim; a job description or requirement; an assessment; or a VET course, try to find an alternative formulation that covers them all together.

Conversely, if a currently lowest-level ability concept has parts that could realistically be claimed, evidenced, required, assessed and trained separately, define those narrower constituent sub-abilities (Form A), and the structure that links the wider and narrower definitions (Form B).

Listing steps to do something, as in task analysis, is only useful if each step is associated with a substantially different set of abilities. If two steps require the same abilities, do not list them separately. You are trying to document the abilities required to do jobs properly, not to write procedures for how to do particular jobs. The two are related, but need distinguishing. Rather than task analysis, what is needed is closer to what is called “functional analysis” by Carroll & Boutall (2011) in their “Guide to Developing NOS”).

Check to see if any of your ability items are covered by broader ones that you have also defined. If they are, ensure that they are placed in suitable hierarchical relationship in your structure.

If one has a job description or set of requirements to hand, it may be possible to proceed in the following fashion.

On the other hand, when starting from an educational syllabus point of view, the above approach is unlikely to work, and an alternative possibility is as follows.

As granularity has been mentioned several times above, it may be helpful to review the different granularities of ability items (or more generally, competence definitions) for different purposes.

The most obvious direct use of an ECS is for potential employers to gain an overview of the skills and competences to be expected from a candidate with a particular vocational qualification. Knowing that employers typically want to do things quickly, the main requirement would be to convey the maximum amount of easy-to-process information in the minimum space. This requirement probably lies behind the ECS guidance, suggesting 5 to 15 items within Section 3.

This requirement is not at all the same as for planning a VET course. Typically a course specification would need to be given much more detail. More detail would also be needed for an assessment specification, along with the assessment criteria, or the “rubric” as it is sometimes called, against which learners are assessed. Assessment is not confined to educational institutions, as an employer’s review and appraisal process also contains a form of assessment. For appraisal and review, a structure would need to have definitions, and level criteria if applicable, that are as clear as possible, and able to be evaluated objectively.

For higher education assessment, there is a clear sense that intended learning outcomes for a course should be few — the numbers 3, 4 and 5 come up in conversation — so that each intended learning outcome can be properly assessed within the constraints of a formal assessment process. However, this small number of intended learning outcomes would not be ideal for planning a course in detail. The question then remains, how will the intended learning outcomes be related to the detailed curriculum or syllabus?

For assessment for vocational qualifications, there are fewer constraints. Any reasonable number of abilities can be checked, provided that they can be observed and assessed by an assessor.

One option that could be taken is to create separate structures for the different uses, and this has often been done. However, this is not ideal for interoperability of tools, or mobility of people. A better approach might be to create an overall structure giving all relevant granularities, and choose the appropriate granularity for each use.

Even though it may not be easy to create an integrated structure that serves all required purposes at once, this is the ideal recommended procedure. One could start by laying out all the different uses, and for each different use, write down a formulation of the ability item short descriptions that serve each purpose. If items for one purpose are the same as, or strict parts of, items for another purpose, all well and good. If the items relate only awkwardly, it will be a matter of negotiation to adjust them so that all the purposes are adequately fulfilled, using only items from a single, clear, hierarchy.

We are now in a position to review the official ECS guidance, and reflect on the possible reasons behind each point.

With the exception of the first point, which has been discussed above under the heading of granularity, all the rest of these points seem reasonable and sensible for all competence and ability definitions.

Of the issues that have been addressed above in the high-level model, one other point stands out: the issue of optionality. Currently there is no standard way of representing optionality within a Europass Certificate Supplement. If there were options in a vocational course leading to a ECS, some compromise solution will have to be adopted. Here are some suggestions for possible solutions.

The ELP has its own well-defined framework of “language proficiency”, given in the self-assessment grid within the template. There are five distinct areas of proficiency: listening; reading; spoken interaction; spoken production; and writing. Listening and reading fall under the broader heading of “understanding”, while spoken production and spoken interaction fall under the broader heading of “speaking”. One could formulate generally useful ability items by rephrasing the area of proficiency and adding a specific language: e.g. “interact through speech in French”. One could perhaps use Form A to define ability items in these various areas, for each language of interest, but they would only be useful when levels are added.

The level of ability or proficiency reached by an individual is very significant for employment and many other reasons. The ELP defines six levels (A1 to C2) for each area of proficiency, therefore 30 self-assessment descriptors in total. For instance, level B1 of proficiency in spoken interaction is given the descriptor: “I can deal with most situations likely to arise whilst travelling in an area where the language is spoken. I can enter unprepared into conversation on topics that are familiar, of personal interest or pertinent to everyday life (e.g. family, hobbies, work, travel and current events).”

The ELP levels could be represented with 5 instances of Form C (introduced above). Rephrasing slightly for generality and to avoid the first person, the spoken interaction proficiency levels could be given perhaps like this. As in previous examples, the level numbers are purely invented, to allow potential finer distinctions, and to allow for numbers to represent the possible level id codes “A” (basic user), “B” (independent user) and “C” (proficient user). Once defined, however, it is essential that the numbers remain unaltered.

Table 6: Form C for a generic language ability

|

Form C: eCOTOOL high-level model level definition |

|||

|

ability item |

spoken interaction (could be rephrased as e.g. “interact through speech”) in a given language |

||

| unique |

Europass-LP-SI (invented for use here) |

||

| author/authority |

Council of Europe and CEDEFOP |

||

| where level |

http://europass.cedefop.europa.eu/en/documents/european-skills-passport/language-passport |

||

| levels |

definition of each level |

level |

level number |

|

|

Interact in a simple way provided the other person is prepared to repeat or rephrase things at a slower rate of speech and help the subject formulate what the other is trying to say. Ask and answer simple questions in areas of immediate need or on very familiar topics. |

A1 |

10 |

|

|

Communicate in simple and routine tasks requiring a simple and direct exchange of information on familiar topics and activities. Handle very short social exchanges, even though the subject can't usually understand enough to keep the conversation going. |

A2 |

20 |

|

|

Deal with most situations likely to arise whilst travelling in an area where the language is spoken. Enter unprepared into conversation on topics that are familiar, of personal interest or pertinent to everyday life (e.g. family, hobbies, work, travel and current events) |

B1 |

30 |

|

|

Interact with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that makes regular interaction with native speakers quite possible. Take an active part in discussion in familiar contexts, accounting for and sustaining the subject’s views. |

B2 |

40 |

|

|

Express self fluently and spontaneously without much obvious searching for expressions. Use language flexibly and effectively for social and professional purposes. Formulate ideas and opinions with precision and relate my contribution skilfully to those of other speakers. |

C1 |

50 |

|

|

Take part effortlessly in any conversation or discussion and have a good familiarity with idiomatic expressions and colloquialisms. Express self fluently and convey finer shades of meaning precisely. If a problem arises, backtrack and restructure around the difficulty so smoothly that other people are hardly aware of it. |

C2 |

60 |

It would appear to be quite difficult, and rather awkward if attempted, to treat each of these level definitions as an ability item in its own right. If any further detailing were needed, it might be better to restructure the level definitions entirely.

Given this and four other similar tables acting as definitions, it becomes clearly possible to apply these categories to claims, to job requirements, to course learning outcomes, prerequisites, etc. They are not, however, best formulated for use within a Certificate Supplement.

There are three places in the ECV where competence-related information may be given. First, in the work experience section, there is space for “main activities and responsibilities”, and entries here could correspond to broad items in a competence framework. Second, in the education and training section, there is space for “principal subjects/occupational skills covered”, which clearly may correspond to items in a framework of the kind discussed here. Third, there is the personal skills and competencies section. This combines part of the Language Passport with a set of skill or competence categories unique to the ECV. Beyond languages, these are:

It would make little or no sense to treat these as ability items in their own right, as they are too general to be used directly as abilities claimed or required. Rather, this section as a whole, together with the spaces in the work experience and education and training sections, invite people to list ability items that are defined elsewhere.

The EDS does not mandate the representation of skills and competences as such. However, the EDS Section 4.3 (programme details) abilities could potentially be referenced. The units or modules detailed in Section 4.3 may have intended learning outcomes that are in effect eCOTOOL competence model ability items. Alternatively, if skills or competences are directly assessed as required parts of a degree programme, these might possibly appear in Section 4.3. Levels of these abilities could be defined (e.g. using our Form C), and an assessment mark for the ability could then refer to this level scale.

The EDS section 6.1 can also be used to record awards (possibly including assessment) related to skills and competences not within the core degree programme.

The eCOTOOL competence model supports the representation of ability items across all Europass documents through insisting that every ability item has a unique id code. The unique id codes should be made into a fixed and stable URIs, and each URI, when entered into a browser, should resolve to a page from which information about the identified ability item can be found. On all electronic documents, an ideal approach would be to list the short description of the ability item as a link to its own proper URI.

The eCOTOOL Technical Competence Model adds extra detail on top of the high-level model, so as to provide the detailed underlying connections and the information model, ultimately to help with the design and interoperability of ICT-based competence services.

The eCOTOOL Competence Model (Technical) consists of:

This section introduces terms that will be used later, in preparation for the exposition of the model. These definitions are additional to the ones already given above for the high-level model.

Assessing body: organisation that assesses or evaluates the actions or products of learners that indicate their knowledge, skill, competence, or any expected learning outcome [CWA 16133]

Assessment process: process of applying an assessment specification to a specific learner at a specific time or over a specific time interval [CWA 16133]

Assessment result: recorded result of an assessment process [EN 15981]

Assessment specification: description of methods used to evaluate learners' achievement of expected learning outcomes [CWA 16133]

Awarding body: organisation that awards credit or qualifications [EN 15981]

Educational framework: system of concepts, definitions and provisions through which educational practices are ordered, related and articulated [EN 15981 “framework”]

Effect, product: material result of a learner’s activity

Generic work role: type of job commonly understood

across an occupational domain

(Short phrases for these could typically be used in job advertisements, job

specifications, and occupational frameworks and standards.)

Industry sector: system of employers, employees and jobs working in related areas

Intended learning outcome: statement of what a learner is expected to know, understand, or be able to do after successful completion of a learning opportunity [adapted from ECTS Users Guide]

Job description or requirement: expression describing or implying the abilities required to perform a particular job or role

Learning outcome: see intended learning

outcome

(unintended learning outcomes may be many and varied, highly

dependent on the individual learner)

Level attribution: application of a level id code and/or number from a specified level scheme to an ability concept

Level id code: term used to identify a level

Level number: numeric level term, or number associated with a level, where a larger number means greater ability, allowing inferences to be drawn between levels

National/regional authority: organisation that regulates and/or validates the learning processes leading up to, or the acquisition of, the Europass Certificate Supplement

Occupational standard: formulation of the skills,

knowledge, understanding and judgement needed to perform particular roles or

jobs in accordance with agreed criteria

(Different criteria may be defined for different occupational levels.)

Personal claim: statement that a learner has

defined abilities

(This is typically detailed to clarify aspects not fully explained in the

definitions used, and the claim is then supported by evidence.)

Progression: process which enables learners to pass from one stage of learning to the next and to access learning opportunities that prepare for qualifications at a higher level than those they already possess [adapted from ECTS Users Guide]

Progression pathway: series of learning opportunities taken, along with qualifications and learning outcomes achieved, directed towards learner goals

Progression rules: set of rules that define conditions for learners’ progression within qualifications and towards other qualifications [ECTS Users Guide]

Qualification: status awarded to or conferred on a

learner

(Many formal learning opportunities are designed to prepare learners for the

assessment that may lead to an awarding body awarding them a qualification.) [EN

15982]

VET body: body that manages or provides learning education or training in the vocational sector

Looking back to the high-level model, explained above, its purpose is to give people relatively straightforward and effective tools to facilitate the recording of information relevant to competence concepts and structures. It is presented in an easy-to-visualise form that can be printed and filled in on paper. However, presentation in a paper-oriented, visual way tends not to make explicit the inherent structure of the information. There is only an implicit structure in the paper-based form. The advantage of the structure being implicit is that the representation is more straightforward to understand, but for preparing the information for real use in an ICT system the implicit structure needs to be made explicit.

In addition, some simplifying assumptions have been made for use with the high-level model, and it is important to undo these so that people working with fully structured electronic representations are not unnecessarily constrained.

The three Forms, A, B and C, of the high-level model give a good foundation for a technical model. Form A represents the ability or competence concept itself, seen separately from other related concepts. This will be treated first. Form B represents the structural relationships between the competence concepts, and this will be treated next. Form C covers the definition of levels, and this will follow.

In the use of Forms B and C, there is no clear requirement that all the parts, or levels, listed in the Forms must have their own Form A. But to produce a clean information model, designed for ease of technical implementation, this is necessary, and this will be explained at the appropriate place.

For representing a whole framework or structure of related competence concept definitions, the paper-form analogy suggests that a framework is represented in terms of a set of forms. Indeed, it is normal for all the above information to be assembled together into frameworks, sometimes thought of as, and called, occupational standards. In the eCOTOOL competence model, for clarity and consistency, these will be referred to as frameworks, recognising that other terms are also used elsewhere. There is also potential information relating to the framework itself, rather than to its constituent definitions and relationships, and this information was not allowed for in the high-level model. An explanation of representing frameworks will therefore follow the explanations of the concept definitions and the relationships.

Having clarified the representation of frameworks, it remains finally to give an account of how to represent relations between concepts in different frameworks. This includes the case of one framework including concept definitions originally defined within a different framework.

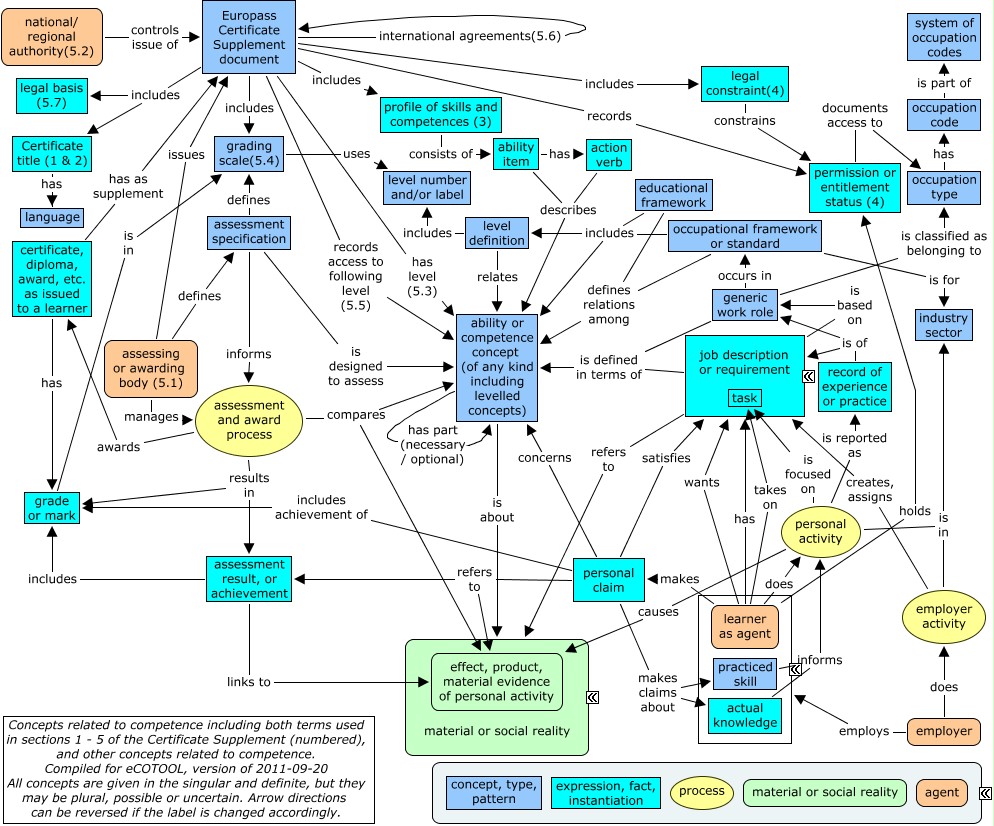

The following diagram is an attempt to illustrate the concepts surrounding an ability or competence concept, in preparation for the definition of the information model. At the top left of the diagram is represented the Section 3 of the Europass Certificate Supplement, the “Profile of Skills and Competences”. As explained previously, each line in the ECS Section 3 is referred to here as an “ability item”. Each ability item should normally (but in practice does not always) have an action verb. The ability item is one description of the underlying concept, and from here on the focus in on the concept itself, the “ability”, so that we can look beyond any particular form of words that may be used to describe it.

Educational and occupational frameworks include descriptions (in their own terms) of relevant ability or competence concepts, but also usually they describe the relationships between them, (including which ability is a part of which other ability) and they often also define levels. Level definitions will be described in more detail below. Particular job descriptions, as well as generic work roles, are typically described in terms of what people have to be able to do. Specified assessments may assess given abilities that people have, and an assessment process typically compares the available, allowed evidence of personal performance against descriptions of the relevant ability. Whether backed up by formal assessment or just self-assessment, people make personal claims to have abilities.

Distinguishing these other concepts surrounding the ability or competence concept makes it easier to focus on what needs to be represented to express a particular ability, separately from representing the surrounding concepts.

Figure 1: Significant concepts surrounding ability or competence

The arrows in this map leading in towards the ability or competence concept also illustrate potential uses of the concepts. Apart from the use in the ECS Section 3, the map indicates that ability or competence concepts can be used: (a) in assessment, in the sense that an assessment is designed to assess a person’s ability in the given area, and the assessment process compares the evidence of a person’s activity with the concepts; (b) in personal claims; (c) in job descriptions or requirements; and (d) in occupational frameworks or standards (which themselves may mention generic work roles). Not illustrated in the maps is their potential use (e) in courses of learning, education or training.

An ability item short description, as appearing in Section 3 of the ECS, is one way of expressing in words an ability or competence concept, but not the only way: that concept can also be defined in more detail. To play a part in a fuller information structure, and to support the creation of ICT tools and services, this section proposes a more detailed structure for such definitions. The term preferred, “competence concept definition”, is intended to cover the competence-related concepts of ability, skill and knowledge, as well as competency and competence.